CEMAC: Joint ownership of boats Increases illegal fishing

CEMAC: Joint ownership of boats Increases illegal fishing

The absence of an efficient local industry and a lack of capital has led to foreign operators dominating the fishing sector in Cameroon, Congo and Gabon . These companies forge partnerships with local operators, disguising their identity and real profits. In Cameroon, for example, almost 85 tonnes of fish caught fraudulently was seized in 2023, generating estimated tax losses of 20 billion Cfa francs a year.

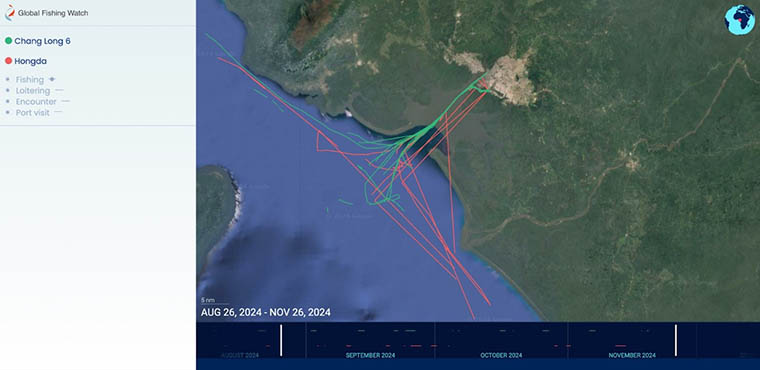

On the morning of 13 September 2024 in the port of Douala, the Chang Long 6, with its faded and rusty superstructure, empties the contents of its hold. Men are busy on the upper deck of this longliner, which has spent 10 days at sea according to geo-positioning data from Global Fishing Watch, a website specialising in monitoring fishing activities worldwide, Global Fishing Watch.

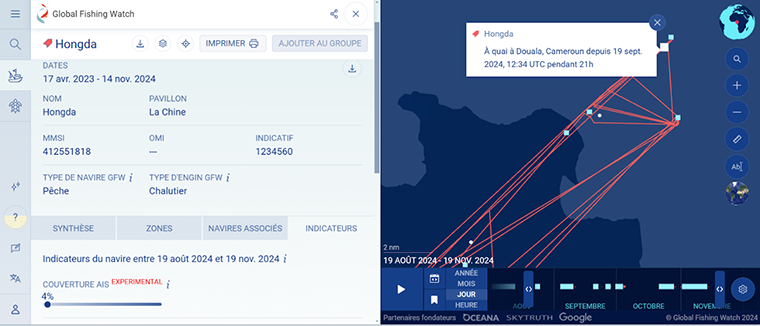

Alongside this vessel, another vessel called Hong Da, whose identification number is concealed by the workers unloading the seafood. These two vessels are well known in the fishing port of Douala, as vessels with the same name but different numbers regularly dock there.

According to the Ministry of Livestock, Fisheries and Animal Industries (MINEPIA), the average quantity of fish products landed is 10 to 12 tonnes per vessel per trip (a trip lasts around 8 days). 70% of catches are sent to Yaoundé, 30% to Douala and other regions. The shrimp are frozen and exported to Asia.

The Japan Cooperation Report of 2023 on fisheries in Cameroon also shows that national fisheries production has risen from 200 000 tonnes in 2013 to 340 000 tonnes in 2019. According to the report, the main product exported, shrimp, is mostly sold in the Asia-Pacific region (Malaysia, Vietnam, Taiwan, Australia, etc.).

An analysis of the traffic history of the two fishing vessels mentioned above on the Global Fishing Watch platform reveals that Chang long 6, of unknown origin, has been seen on the Cameroonian coast since 12 April 2022. It made 31 voyages between that date and 17 September 2024, with 31 visits to the port of Douala, including 9 between July and October 2024. The Chinese trawler Hong Da, made 8 trips over the same period. These two vessels are on the list of vessels that have been granted a fishing licence by MINEPIA in 2023 and 2024.

Given that the Cameroonian law prohibits foreign ownership of vessels, foreign investors opt to set up joint ventures with domestic players to circumvent the regulatory hurdle. A solution that is accepted by the legislation. Steve Trent, co-founding CEO of the Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF), a British NGO campaigning for environmental protection explains that, “Several countries in the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) (Cemac) authorise foreign participation by allowing the creation of joint ventures between national and foreign investors”.

Collaborative contract

This expert adds that “vessels belonging to joint ventures apply for a local fishing licence through the local partner, and these arrangements allow them to register under a local flagship, even if they are partly or wholly foreign-owned”. According to MINEPIA’s list in Cameroon, this is relevant for Hong Da, the name given to a fleet of at least 5 vessels (Hong Da 2, Hong Da 18, Hong Da 6…), owned by Bertin Boukagne, a Cameroonian. However, Global Fishing Watch files shows that the vessel is flying a Chinese flag, suggesting links with China. The main players in industrial fishing resort to this practice in the waters of Cameroon, Gabon and Congo.

Bertin Boukagne is the owner of Ets éponymes, one of the 9 industrial fishing companies registered in Cameroon in 2023. These companies operate a total of 35 fishing vessels with fishing licences issued by MINEPIA in 2023. Ets Boukagne Bertin has a berth in the towns of Limbé, Douala and Kribi. In 2024, Bertin Boukagne obtained a fishing licence for a fleet of 9 vessels.

The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) explains in its report on fisheries that “all fishing vessels operating in Cameroon today are owned by foreign companies, and enter Cameroon under a bareboat chartering regime. A national company manages the national administrative side of the partnership, and is remunerated on the basis of a contract between the two companies, which provides for a fixed monthly fee per vessel managed.”

According to Steve Trent, “Joint ventures involving foreign investors are legitimate as they enable coastal countries lacking capital, infrastructure and markets to develop their own industrial fishing industries with the support of foreign funds”. Unfortunately, he explains that, these joint ventures pave the way for shady deals that encourage illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUU). He adds that “the of transparency in global fisheries has also led to the creation of many fictitious joint ventures, where the local partner serves only as a ‘front’ or agent for the foreign investor who really owns the business”.

National Companies

Like China’s Hong Da, most of the vessels fishing in the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of CEMAC countries are of foreign origin. According to EJF’s 2023 report , 63% of the boats in Cameroon in 2023 were owned by foreigners. Out of 171 vessels, only 66 are registered in Cameroon. That is 107 of foreign origin linked to 32 different jurisdictions.

This information corroborates that of the Center for Advanced Defense Study (C4ADS), an organisation specialised in the analysis of transnational security data. The data analysed shows that Spain and China are the main countries of origin of the fishing vessels identified in the Cameroonian, Gabonese and Congolese waters between 2019 and 2023.

In the Congo, Chinese-flagged vessels account for 25.7%, followed by Spanish vessels (22.8%). Jean Michel Dziengue Toddy, a fisheries management consultant in the Congo explains that “the strong presence of foreign fishing vessels on the coasts of Cameroon, Gabon and the Congo can be explained by the fact that the governments do not support national fishing companies. In the case of the Congo, there was a national fishing company, but it also closed down due to insufficient funds to renew the fishing equipment (fishing vessels).

In Gabonese waters, there are a large number of Spanish vessels, followed by France. China, with 14.4%, comes third. The data also show that Cameroon has the highest number of vessels in its territorial waters, with 105 observed between 2019 and 2023. Gabon comes second with 75 vessels, ahead of Congo (35).

An analysis of MINEPIA and C4ADS data shows that in some cases, several fishing vessels in Cameroon, Congo and Gabon have the same owners. This is the case of Rodriguez Mariscos, a Spanish businessman with a strong presence in Congo and Gabon. Like Bertin Boukagne in Cameroon, he is the sole owner of seven of the thirty vessels identified by C4ADS in Congo and 6 in Gabon. These are mainly San Jorge R, Jaime R, La Pinta R, Mazagon R, Torredeloro R, Andres R and Virgen Milagro R. He is one of the directors of Mariscos Rodriguez SA, one of whose activities is sea fishing.

This model of business partnerships between nationals and foreigners also encourages illegal practices and dubious activities. According to Steve Trent, “the problem is not the registration of foreign vessels. This is how some countries facilitate secrecy as regards the real ownership of vessels, which means that the benefits of fishing in Cameroonian waters disappear beyond its borders in many cases, offering nothing to Cameroonians other than declining fish populations for their own fishermen”.

In 2023, EJF recorded 18 vessels of unknown origin in Cameroon. The data from Global Fishing Watch and C4ADS show unidentified vessels operating in the economic zones of these three CEMAC countries. This gap is sometimes created by the fact that these vessels have potentially changed their flag. Another recurring practice adopted by shipowners is when the vessel has been sanctioned in a particular country. This enables them to disguise the ship’s history. Once registered, the ship can change its registration number as well as its name. The co-founder of the EJF explains that, “even countries that have put in place a certain level of control over the compliance history of ships can still be deceived by the more general lack of transparency”.

Flaws in the System

Even with reliable information, some vessels with a record of IUU fishing still go unnoticed by the authorities. At least, they continue to operate in Gabon, Congo and Cameroon. The Haixin 27 is present in all three countries. However, it was apprehended in 2019 by the Gabonese army on its way from Congo. Its ship was full of fish, even though it wasn’t authorised to fish. The Hong Da 2, a vessel licensed to fish in Cameroon in 2023, was fined by the Peruvian Ministry of Production. The vessel had not submitted the required documents in the format and in accordance with the regulations in force.

According to Baba Inoussa, a researcher and fishing specialist, Cameroon is experiencing a lack of cooperation between the Ministry of Transport (MINT) which issues vessel registrations, and the Ministry of Fisheries. He explains that “the problem that often arises is that boat promoters go directly to the Ministry of Transport to obtain authorisation for any floating equipment, and this is often done without consulting MINEPIA”.

This lack of collaboration is acknowledged by Elie Badai, head of MINEPIA’s fisheries control and surveillance brigade, with whom the team of reporters met during a seminar in May 2024. “Concerning registration, we suggested that there should be good collaboration between Ministry of Transports and ours for the registration of fishing vessels. What is important about fishing vessels is their history, which can influence the allocation of the flag,” he explains.

EJF also highlights countries’ lack of transparency in this sector. “Information on who fishes what, when and how is often not made public, and is also rarely shared between countries. Regional fisheries bodies have not proved effective in addressing these deficiencies. Many CEMAC countries do not publish crucial information about vessels operating in their waters, including details of sanctions for illegal fishing and fishing-related crime. In addition, information on the ownership of vessels is often not made public’, regrets the head of EJF.

Vessels with a history of IUU fishing are numerous in industrial fishing. Data collected by C4ADS show that a total of 20 vessels with either suspected IUU fishing or indicators of risk of illegal fishing entered Gabon’s EEZ between 2019 and 2023. Of these 20 vessels, almost half (9) is of Spanish origin. Paradoxically, Spain is one of the countries offering assistance with maritime surveillance in the waters of the Gulf of Guinea.

The 20 vessels with a record of IUU fishing that entered Gabon’s exclusive economic zone are ultimately owned by Spain, France, China and the Bahamas. The vessels in question were notified for non-compliance with licences, failure to declare catches and failure to provide the appropriate documents.

Environmental Threat

Illegal fishing practices are encouraged by lax legislation that is ill adapted to the phenomenon and by a lack of resources on the part of fishing authorities to carry out controls. By law, these practices include failure to respect fishing zones. “In Cameroon, according to the law, fishing boats had to start fishing from three miles out, i.e. 4 kilometres from the coast, but nowadays we generally find boats fishing further out,” observes Baba Inoussa.

This is also the observation of the FAO, which notes in its report cited above that ‘the three nautical mile exclusion zone for trawlers (…) is regularly transgressed and illegal trawling is carried out in these waters. This leads to direct conflicts with small-scale fishing, with trawlers destroying the passive nets of small-scale fishermen, which are often poorly marked”. In addition to this, vessels are also guilty of under-reporting catches and transhipments at sea, which make it “difficult to track the supply chain of the fish caught, and can conceal illegal fishing,’ stresses EJF.

Analysis of C4ADS data reveals that trawlers are still the most commonly used type of vessel in the 3 countries, despite warnings of the dangers they pose to the environment . Out of 105 vessels recorded in Cameroonian waters over the last 5 years, the majority (83) are trawlers. Most of these trawlers use nets that have been modified with illegal mesh sizes, resulting in the capture of small fish.

Baba Inoussa affirms that “the law recommends that for all towed gear, the mesh coverage should be between 40 miles (4 cm) from the cod end (the area where species are concentrated and caught) of the trawler for shrimp fishing, and 50 nautical metres for fish”. But in the field, “by-catches that are discarded vary between 40 and 92% by trawl. In other words, for a troll that spends 6 hours in the water, after sorting, what is discarded often makes up 40 to 92% of the catch. This is excessive because, by-catches should not be more than 30% of the catch,” deplores the expert.

Absence of Laws

In Cameroon, the Ministry of Livestock, Fisheries and Animal Industries (MINEPIA) reports having seized 85 tonnes of fish caught illegally in 2023. According to the Ministry, the total tax loss from IUU fishing is estimated at 20 billion CFA francs a year. With local demand estimated at 500 000 tonnes of fish, local production is estimated at 200 000 tonnes per year. To make up this shortfall of nearly 300 000 tonnes, the government spends more than 100 billion CFA francs a year on fish imports.

According to the Gulf of Guinea Regional Fisheries Commission, fraudulent fishing accounts for almost a quarter of Africa’s total annual fish exports. Annual economic losses are estimated at more than 2.3 billion dollars, or around 1400 billion Cfa francs.

Stève Trent states that, unscrupulous operators are attracted by systemic failings in fisheries governance. This means that illegal fishing and overfishing are likely to remain undetected. In several CEMAC countries, the law favours certain practices. This is either because there is a legal vacuum on certain aspects, or because they are incomplete. In Cameroon, the law on fishing is currently being revised.

Besides being more than 30 years old, this law is considered to be incomplete in terms of content. Out of the approximately twenty pages that make up this document, only a few passages address fishing issues, while entire chapters are devoted to forestry or hunting. “It would be appropriate to revise this legal framework to incorporate instruments that comply with international standards, thereby facilitating the fight against IUU fishing’s, says Eddy Nnanga, a fisheries engineer and coordinator of projects on Marine Protected Areas and Wetlands at the African Marine Mammal Conservation Organization (AMMCO).

Apart from regulations, another factor that encourages IUU fishing is the procedure for granting fishing licences. In CEMAC countries, civil society organisations are highlighting irregularities. “In the Congo, there is no transparency in the allocation of fishing licences. There are many cases of corruption in the allocation of licences (industrial fishing) and fishing permits (small-scale fishing)”, says Jean Michel Dziengue Toddy.

EJF recommends that national and regional governments regularly publish relevant information on vessels operating in their waters, including sanctions for IUU fishing and fishing-related crimes, as well as details of vessel ownership . “States should strengthen their surveillance mechanisms against IUU fishing and, above all, incorporate the Global Charter for Transparency into their national legislation,” suggests Steve Trent.

According to MINEPIA, resources need to be strengthened because they are insufficient to ensure the control and monitoring of fishing activities. Car, ils sont insuffisants pour assurer le contrôle et la surveillance des activités de pêche. “Cameroon had a system for monitoring, controlling and surveillance of activities via the VMS and the Automatic Identification System (AIS). Unfortunately, their systems have been hacked and as a result we’re virtually back to square one . This year, thanks to our activities, the Minister has agreed to acquire a new system. We expect to have it by the end of the year, and to acquire beacons in the new system we have and update our new VMS system’s, explains Dr Elie Badai. He adds that surveillance requires a lot of resources, which are difficult to mobilise.

As part of this survey, all our efforts to contact the Ministry of Transport and Ministry of livestock, Fisheries and Animal Industries have been in vain.

Tatiana MELIEDJE Y., Marie Louise MAMGUE, Ludovic AMARA

This work was carried out as part of the second cohort of the Project to Investigate the Governance of Natural Resources in Central Africa (ODACA), initiated by ADISI-Cameroon with technical support from DataCameroon.